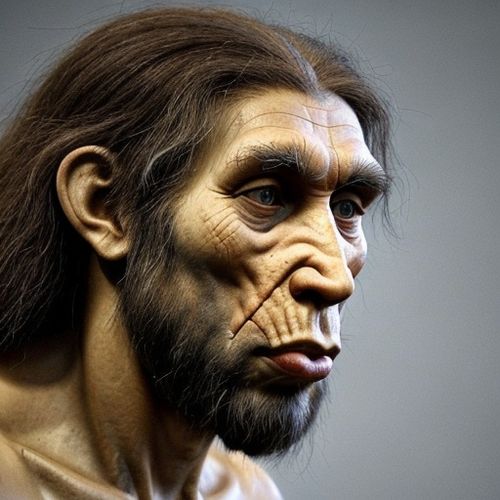

The discovery of a 31,000-year-old skeleton with evidence of a successful leg amputation has rewritten the history of surgery. Found in a limestone cave in Borneo, this remarkable find pushes back the origins of complex medical procedures by tens of thousands of years, revealing that ancient humans possessed sophisticated knowledge of anatomy and wound care long before the advent of agriculture or formal medical systems.

Buried in Liang Tebo cave, the skeletal remains belong to a young individual who survived for several years after losing their left foot and part of the lower leg. What makes this case extraordinary isn't just the prehistoric timing, but the clean, healed bone surface showing no signs of infection - clear evidence this was no accidental injury but a deliberate surgical act. The bone's growth patterns suggest the amputation occurred during childhood, with the individual living into early adulthood as a valued member of their community.

Archaeologists initially doubted their own findings. "The smooth bone remodeling left no question - this person received careful postoperative care," noted lead researcher Dr. Melandri Vlok from the University of Sydney. The surgical precision contradicts assumptions about Paleolithic life, proving these hunter-gatherers understood blood flow restriction, antiseptic techniques, and pain management - knowledge we previously believed emerged with settled civilizations.

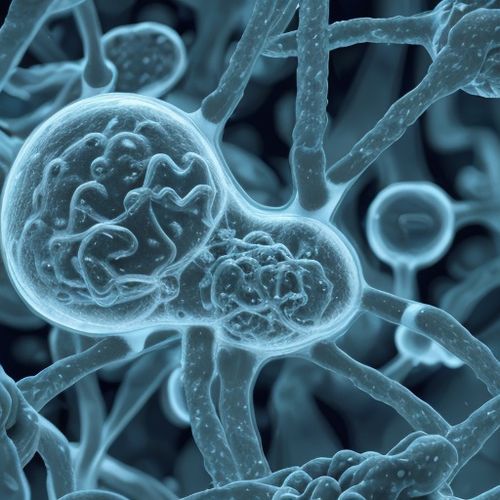

The tropical environment makes the survival even more astonishing. In humid conditions where even minor wounds easily fester, this community somehow prevented lethal infection. They likely used medicinal plants from Borneo's biodiverse rainforests - perhaps early ancestors of today's antimicrobial tropical remedies. The patient's continued survival indicates they were provided food and protection during years of recovery, hinting at compassionate social structures.

This discovery shatters Eurocentric medical timelines that credited ancient Egyptians or Greeks with pioneering surgery. The Borneo amputation predates the previous oldest known surgical example - a 7,000-year-old Neolithic skull trepanation - by 24,000 years. It suggests medical knowledge developed independently among diverse prehistoric cultures, with tropical regions possibly advancing wound treatment earlier due to greater infection risks.

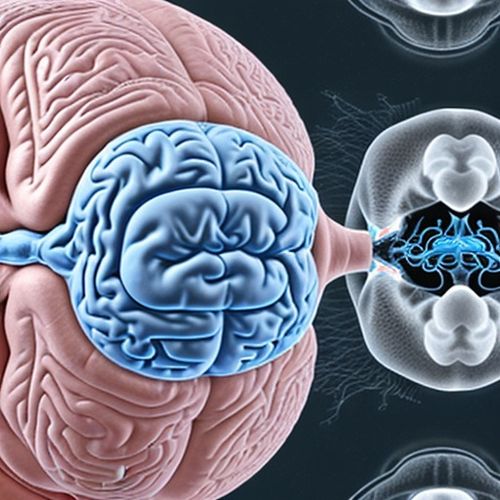

Forensic analysis reveals the surgeon's skill. The clean cut through the tibia and fibula avoided damaging the growth plate, allowing the child's leg to continue developing. Such anatomical understanding implies generations of accumulated medical observation. The lack of crushing fractures rules out animal attacks or ritual punishment, while the angled bone surface confirms use of sharp stone tools - perhaps obsidian blades known for their surgical precision.

Why amputation rather than mercy killing? The community's choice reflects complex cultural values. Some anthropologists suggest this individual's survival indicates early recognition of human rights or spiritual beliefs about bodily integrity. Others propose practical reasons - in tight-knit groups where every member's contribution mattered, investing in a disabled person's recovery might have offered long-term benefits we don't yet understand.

The find has ignited debates about Paleolithic healthcare systems. Previously, we imagined Stone Age medicine as crude and superstitious. This surgery forces us to reconsider - did these people have designated healers? Were there proto-medical schools passing down techniques? The patient's survival implies standardized procedures refined through trial and error over generations, not a one-time miracle.

Modern medicine gains historical perspective from this ancient success. Today's surgeons still follow basic principles demonstrated here: clean cuts, infection control, and rehabilitation. That these fundamentals were mastered during the last Ice Age humbles our technological arrogance. Perhaps prehistoric people, through intimate observation of nature and human anatomy, achieved medical insights we're only now rediscovering through modern science.

As excavations continue in Borneo's caves, researchers hope to find tools or plant residues that might reveal specifics about this lost medical tradition. For now, this single skeleton stands as testament to humanity's long, ingenious struggle against physical suffering - proving that compassion and scientific curiosity are as ancient as our species itself.

By Victoria Gonzalez/Apr 10, 2025

By Joshua Howard/Apr 10, 2025

By Noah Bell/Apr 10, 2025

By Emily Johnson/Apr 10, 2025

By Eric Ward/Apr 10, 2025

By Megan Clark/Apr 10, 2025

By Samuel Cooper/Apr 10, 2025

By Daniel Scott/Apr 10, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 10, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 10, 2025

By Lily Simpson/Apr 10, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 10, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 10, 2025

By Samuel Cooper/Apr 10, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 10, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 10, 2025

By Joshua Howard/Apr 10, 2025