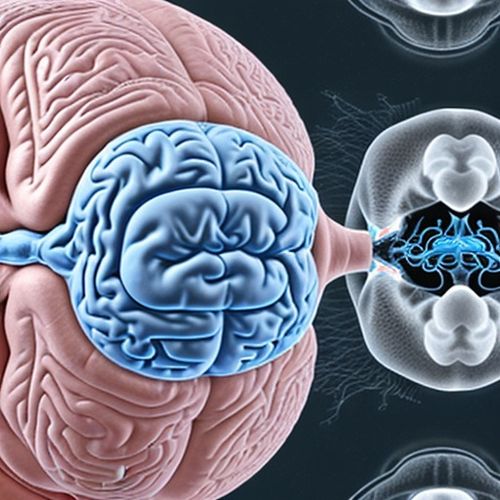

The human brain, a marvel of biological engineering, requires adequate rest to function optimally. Yet, in our fast-paced modern world, sleep often takes a backseat to productivity and entertainment. A groundbreaking study from Stanford University has shed light on a disturbing correlation between chronic sleep deprivation and accelerated brain aging, particularly in individuals who consistently sleep fewer than five hours per night.

For decades, scientists have understood that sleep plays a crucial role in cognitive health. However, the Stanford research provides compelling evidence that insufficient sleep doesn't merely cause temporary fatigue—it may actually rewire the brain's structure and function in ways that mirror the aging process. The implications of these findings are profound, suggesting that our sleep habits today may significantly influence our neurological health decades from now.

The Stanford Sleep Study: Methodology and Key Findings

Conducted over a three-year period, the Stanford study followed nearly 5,000 participants aged 35 to 75, tracking their sleep patterns through wearable devices and conducting regular cognitive assessments. What set this research apart was its use of advanced neuroimaging techniques to measure changes in brain structure and connectivity over time.

The results were startling. Participants who averaged less than five hours of sleep per night showed measurable declines in gray matter volume, particularly in regions associated with memory and decision-making. These structural changes occurred at a rate approximately 30% faster than seen in participants who maintained seven to eight hours of sleep. Essentially, their brains appeared to be aging prematurely.

Why Five Hours Becomes the Critical Threshold

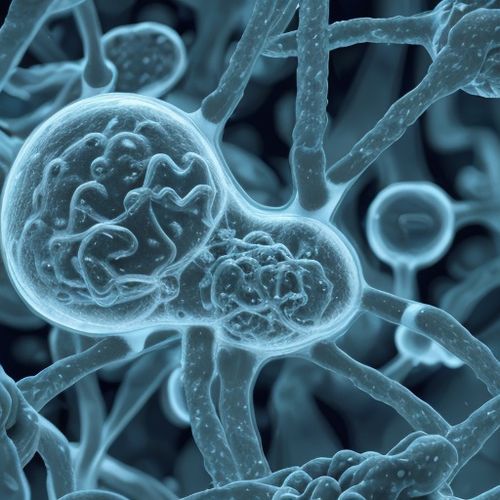

Sleep scientists have long debated the minimum amount of sleep required for brain health. The Stanford findings suggest that five hours may represent a biological tipping point. Below this threshold, the brain's waste clearance system—known as the glymphatic system—becomes significantly less efficient at removing toxic proteins that accumulate during waking hours.

Among these proteins is beta-amyloid, strongly associated with Alzheimer's disease. The study found that sleep-deprived participants had higher concentrations of these harmful compounds, creating an environment conducive to neurodegeneration. This helps explain why chronic short sleepers often exhibit memory problems and cognitive decline earlier in life than their well-rested counterparts.

The Domino Effect of Sleep Loss on Brain Function

Beyond structural changes, the research revealed functional consequences of sleep deprivation. Participants who slept fewer than five hours showed decreased connectivity between the hippocampus (critical for memory formation) and other brain regions. This neural disconnect manifested in real-world performance, with subjects struggling more with complex tasks requiring attention switching and problem-solving.

Perhaps most concerning was the observation that these effects appeared cumulative. Each consecutive night of short sleep seemed to compound the damage, suggesting that "catching up" on weekends might not fully reverse the neurological impact of weekday sleep deprivation. The brain, it appears, requires consistent, adequate rest to maintain its structural integrity and functional capacity.

Modern Lifestyle Factors Exacerbating the Problem

Several contemporary trends have converged to make chronic sleep deprivation a public health crisis. The proliferation of artificial light, particularly from screens, disrupts natural circadian rhythms. Work demands, especially in knowledge economy jobs, often encourage late nights and early mornings. Even leisure activities—binge-watching, social media scrolling—compete with sleep time.

The study noted that many participants significantly underestimated their sleep debt. While self-reports averaged six hours of sleep, wearable data revealed most actually slept closer to four and a half hours. This disconnect between perception and reality makes addressing sleep deficits particularly challenging.

Potential Long-Term Consequences for Public Health

If the Stanford findings hold true across larger populations, we may be facing a neurological time bomb. Accelerated brain aging could lead to earlier onset of dementia and other neurodegenerative conditions. The economic impact—from lost productivity to increased healthcare costs—could be staggering.

Equally troubling is the potential for generational effects. Children and adolescents who grow up in sleep-deprived households may develop poor sleep habits that predispose them to premature brain aging later in life. The study's authors emphasize that sleep education should begin early, much like nutrition and exercise awareness.

Hope on the Horizon: Interventions That May Help

While the findings are concerning, the research also identified protective factors. Participants who maintained good sleep hygiene—consistent bedtimes, dark cool bedrooms, limited screen time before bed—showed less dramatic aging effects even when their total sleep time was modest. This suggests that sleep quality may partially compensate for quantity.

Emerging research on sleep optimization techniques, including targeted deep sleep enhancement, offers promise for mitigating some damage. The study also found that occasional "recovery sleep"—extended rest periods after periods of deprivation—could help restore some neural connectivity, though not completely reverse structural changes.

Rethinking Our Relationship With Sleep

The Stanford study challenges cultural attitudes that equate sleeplessness with productivity and toughness. In reality, skimping on sleep may be stealing years from our cognitive lifespan. As one researcher noted, "We wouldn't expect our smartphones to function indefinitely without recharging, yet we make that unrealistic demand of our brains."

Neuroscientists increasingly view adequate sleep not as luxury, but as non-negotiable maintenance for our most vital organ. The study's most profound implication may be this: In our quest to add hours to our days, we may inadvertently be subtracting years from our minds.

As the research continues, one message comes through clearly: Protecting our sleep is protecting our brains. In a world that never sleeps, choosing to rest may be the most important decision we make for our long-term cognitive health.

By Victoria Gonzalez/Apr 10, 2025

By Joshua Howard/Apr 10, 2025

By Noah Bell/Apr 10, 2025

By Emily Johnson/Apr 10, 2025

By Eric Ward/Apr 10, 2025

By Megan Clark/Apr 10, 2025

By Samuel Cooper/Apr 10, 2025

By Daniel Scott/Apr 10, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 10, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 10, 2025

By Lily Simpson/Apr 10, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 10, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 10, 2025

By Samuel Cooper/Apr 10, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 10, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 10, 2025

By Joshua Howard/Apr 10, 2025