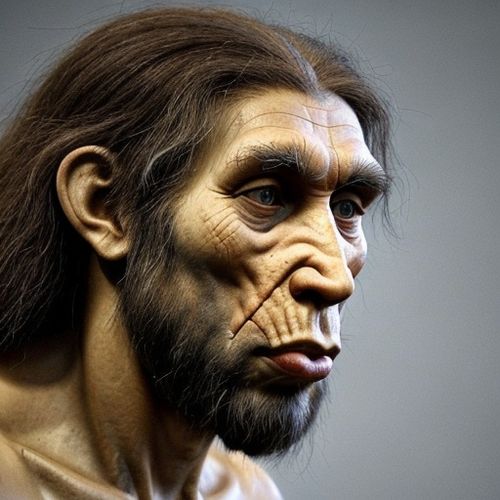

The legacy of our ancient cousins, the Neanderthals, continues to unfold in unexpected ways within our modern DNA. Recent studies have revealed that the genetic contributions from Neanderthals to contemporary human populations are more significant than previously believed. These lingering fragments of archaic DNA are not merely passive remnants of a distant past; they actively influence various aspects of human biology, including susceptibility to certain diseases. One of the most striking findings is the link between Neanderthal DNA and an increased risk of depression in modern humans.

For decades, scientists have been piecing together the complex puzzle of human evolution, and the role of Neanderthals in our genetic makeup has been a particularly intriguing piece. When Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa tens of thousands of years ago, they encountered and interbred with Neanderthals, who had already adapted to the environmental challenges of Eurasia. This intermingling left a lasting imprint on the genomes of non-African populations, with approximately 1-4% of their DNA originating from Neanderthals. While this percentage may seem small, its effects are far from negligible.

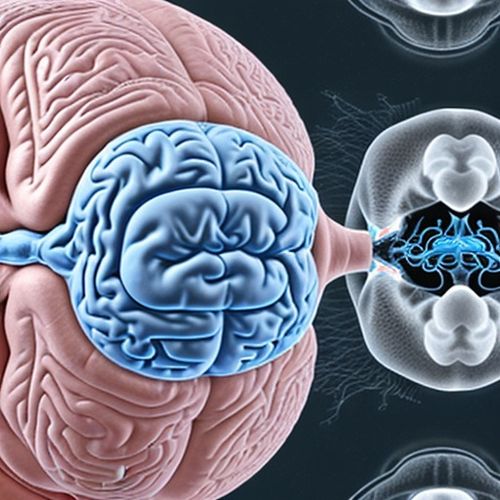

The discovery that Neanderthal DNA influences modern mental health has opened new avenues for understanding the evolutionary roots of psychiatric conditions. Researchers analyzing large genomic datasets have identified specific Neanderthal-derived genetic variants associated with an elevated risk of depression. These variants appear to affect the regulation of neurotransmitters and the functioning of neural circuits involved in mood regulation. It's a sobering reminder that our emotional well-being may be shaped, in part, by genetic echoes from a species that vanished millennia ago.

What makes these findings particularly fascinating is the evolutionary context. The genetic variants that predispose modern humans to depression may have once served adaptive purposes for Neanderthals. Living in the harsh and unpredictable environments of Ice Age Europe, Neanderthals likely faced constant threats and resource scarcity. Certain behavioral traits, such as heightened vigilance or a tendency toward social caution, could have enhanced survival in such conditions. These same traits, when expressed in the context of modern society, might manifest as susceptibility to mood disorders.

The implications of this research extend beyond academic curiosity. Understanding the Neanderthal contributions to our genetic risk factors for depression could lead to more personalized approaches to mental health treatment. By recognizing that some individuals carry these ancient genetic variants, clinicians might better predict treatment responses or develop targeted therapies that account for these deep-rooted biological differences. This knowledge also underscores the importance of considering evolutionary history when studying complex diseases.

However, the story is not as simple as labeling Neanderthal DNA as "bad" for modern humans. Some studies suggest that these ancient genetic contributions may have provided our ancestors with advantages in adapting to new environments outside Africa. The same DNA that increases depression risk might have also conferred benefits related to immune function or metabolism. This duality highlights the complex interplay between evolution and health, where traits that were once advantageous can become maladaptive in different contexts.

The methodology behind these discoveries is equally remarkable. Scientists are now able to compare the genomes of modern humans with high-quality sequences extracted from Neanderthal fossils. Advanced computational tools allow researchers to identify which segments of DNA in living people originated from Neanderthals and then correlate these segments with health outcomes documented in large medical databases. This marriage of paleogenomics and modern epidemiology is revolutionizing our understanding of human biology.

As research progresses, scientists are uncovering more connections between Neanderthal DNA and various traits in modern humans. Beyond depression, these ancient genetic variants have been linked to skin characteristics, immune responses, and even patterns of fat distribution. Each discovery adds another layer to our understanding of how interbreeding with our evolutionary cousins shaped the human species we are today. The Neanderthal legacy within us serves as a powerful reminder that our biology is a mosaic of evolutionary adaptations from different sources.

This growing body of research also raises philosophical questions about what it means to be human. The clear genetic evidence of interbreeding between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals blurs the traditional boundaries we've drawn between species. Rather than being purely "modern" humans, most people outside Africa carry pieces of another human species within their cells. This realization challenges us to reconsider our place in the natural world and our relationship with other hominins who once shared the planet with us.

Looking ahead, scientists are particularly interested in exploring how Neanderthal DNA interacts with modern environmental factors to influence mental health. The increased depression risk associated with these ancient variants might only manifest under certain conditions, such as chronic stress or specific lifestyle factors. Understanding these gene-environment interactions could provide crucial insights into why some individuals are more vulnerable to mental health challenges than others.

The study of Neanderthal DNA in modern humans represents one of the most exciting frontiers in evolutionary medicine. As techniques for ancient DNA analysis continue to improve and genomic datasets grow larger, we can expect to uncover even more connections between our archaic inheritance and contemporary health. These discoveries not only illuminate our past but also offer valuable perspectives for addressing current health challenges. The Neanderthals may be long gone, but their genetic legacy continues to shape human biology in profound and unexpected ways.

By Victoria Gonzalez/Apr 10, 2025

By Joshua Howard/Apr 10, 2025

By Noah Bell/Apr 10, 2025

By Emily Johnson/Apr 10, 2025

By Eric Ward/Apr 10, 2025

By Megan Clark/Apr 10, 2025

By Samuel Cooper/Apr 10, 2025

By Daniel Scott/Apr 10, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 10, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 10, 2025

By Lily Simpson/Apr 10, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 10, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 10, 2025

By Samuel Cooper/Apr 10, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 10, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 10, 2025

By Joshua Howard/Apr 10, 2025